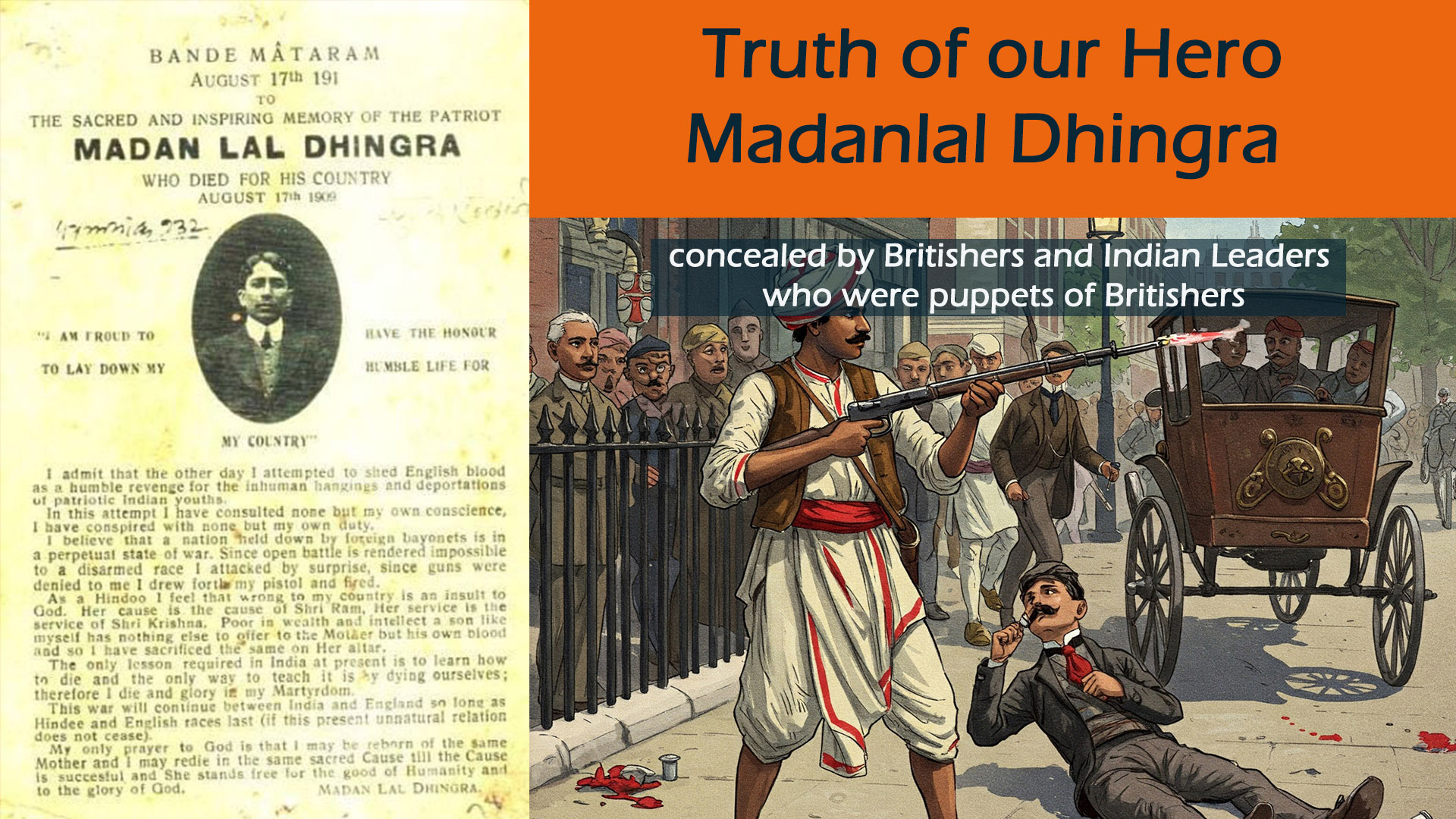

Madan Lal Dhingra, a young Indian revolutionary, shot and killed Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie in London on July 1, 1909. History books and public records claim Dhingra acted out of revenge for British cruelties in India, like inhumane killings or colonial oppression. This is not true. The real reason, deliberately hidden by the British and overlooked in mainstream narratives, is that Curzon Wyllie was a spy who targeted Indian students and revolutionaries in London, especially Dhingra and his mentor, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Dhingra’s act was a bold strike against Wyllie’s secret operations to crush India’s freedom movement. This article uncovers the truth about Wyllie’s spying and why Dhingra had to stop him, written in simple language for everyone to understand.

Who Was Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie?

Curzon Wyllie was a British Indian Army officer who rose to a powerful position as the political aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India, Lord George Hamilton, in 1901. On the surface, he handled diplomatic tasks and managed relations with Indian princely states. But his real job was far more secretive and dangerous for Indian revolutionaries.

- Head of Secret Police: Wyllie was the chief of a secret police unit in London, tasked with spying on Indian students and activists. His mission was to stop the growing freedom movement led by groups like India House, where Dhingra and Savarkar worked.

- Targeting Revolutionaries: Wyllie collected detailed information about Indian nationalists, especially Savarkar, who inspired young Indians to fight for freedom. He used informants and surveillance to track their every move.

- Close to Dhingra’s Family: Wyllie was a friend of Dhingra’s father, Dr. Ditta Mal Dhingra, a loyal British supporter in Amritsar. This connection made Wyllie’s spying even more personal, as he betrayed the trust of Dhingra’s family to monitor the young revolutionary.

Wyllie’s role as a spy made him a direct threat to India’s freedom struggle. He wasn’t just a British officer; he was the “Eye of the Empire,” working to destroy the hopes of young Indians fighting for their country’s independence.

The Truth About Madan Lal Dhingra’s Mission

Madan Lal Dhingra was a 26-year-old engineering student at University College London when he decided to act. Born in Amritsar in 1883 to a wealthy family, Dhingra was deeply troubled by India’s poverty and British exploitation. He joined India House, a center for Indian revolutionaries in London, led by Savarkar and Shyamaji Krishnavarma. There, he learned about Wyllie’s secret activities and realized the danger he posed.

- Wyllie’s Spying Exposed: Dhingra discovered that Wyllie was gathering secret reports on India House members. Wyllie even traveled to Paris to collect information on Savarkar and other activists, aiming to arrest or deport them.

- Using Informants: Wyllie planted spies, like an informer named Kirtikar, inside India House to report on revolutionary plans. This betrayal put Dhingra and his friends at constant risk of being caught.

- Creating a Trap: Wyllie started a “home for London Indians” to lure students and make them loyal to the British. This was a clever disguise to monitor and control young Indians, weakening the freedom movement.

Dhingra knew Wyllie’s spying was suffocating the revolution. If Wyllie succeeded, leaders like Savarkar would be jailed, and India’s fight for freedom would suffer a massive blow. Dhingra decided Wyllie had to be stopped.

Why Dhingra Killed Wyllie

On July 1, 1909, Dhingra attended an “At Home” event hosted by the National Indian Association at the Imperial Institute in London. Wyllie was there, as he often attended such gatherings to keep an eye on Indian students. Dhingra, armed with a Colt pistol, waited for the right moment. As Wyllie left the hall with his wife, Dhingra fired five shots, four hitting Wyllie in the face, killing him instantly. A Parsi doctor, Cawas Lalcaca, tried to intervene and was killed by Dhingra’s sixth and seventh bullets. Dhingra’s act was not about revenge for general British wrongs, as history claims. It was a precise strike to eliminate a dangerous spy.

- Protecting the Revolution: Wyllie’s secret police work threatened to destroy India House and arrest its leaders. Dhingra killed him to protect Savarkar and others, ensuring the freedom movement could continue.

- Sending a Message: By targeting Wyllie, Dhingra showed the British that their spies could not operate with impunity. His act was meant to inspire other Indians to resist British control.

- Personal Betrayal: Wyllie’s friendship with Dhingra’s father made his spying feel like a personal stab in the back. Dhingra, disowned by his father for his revolutionary beliefs, saw Wyllie as a traitor to Indian trust.

Dhingra’s action was not random or driven by blind anger. It was a calculated move to remove a key figure who was choking India’s freedom struggle through espionage.

How the Truth Was Hidden

The British government and media buried the real reason for Wyllie’s killing to protect their image and justify their crackdown on Indian revolutionaries. They painted Dhingra as a reckless murderer driven by hatred for British rule, not as a patriot targeting a spy. This false narrative stuck in history books, hiding Wyllie’s secret role.

- British Cover-Up: The British never admitted Wyllie was a spy. Official reports, like those in the Dictionary of National Biography (1912), called the assassination a “blind, atrocious crime” and ignored Wyllie’s secret police work.

- Media Silence: Contemporary British newspapers avoided mentioning Wyllie’s spying, focusing instead on Dhingra’s “anti-British” motives. This was deliberate to hide the truth and prevent sympathy for Dhingra’s cause.

- Destroyed Evidence: During Dhingra’s trial, he mentioned a letter in his trousers explaining his reasons, but the British destroyed it to suppress the truth. A copy leaked through Savarkar’s friend at the Daily News, but it was not enough to change the public story.

Even Indian leaders like Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi helped hide the truth. Gandhi called Dhingra’s act “cowardly” and said it harmed India’s cause, ignoring Wyllie’s spying and Dhingra’s mission to protect the revolution. This ensured the false narrative of Dhingra as a misguided extremist became the accepted version.

Dhingra’s Sacrifice and Legacy

Dhingra was arrested immediately after the shooting. At his trial on July 23, 1909, at the Old Bailey, he represented himself and refused to recognize the British court’s authority. He boldly declared, “I do not regret killing Curzon Wyllie, as he had played his part in order to set India free from the inhuman British rule.” He was sentenced to death and hanged on August 17, 1909, at Pentonville Prison, at just 24 years old. His family, loyal to the British, disowned him and refused to claim his body, which was cremated in India only in 1976.

- A Hero’s Stand: Dhingra’s courage inspired countless Indians. The Abhinav Bharat Society, led by Savarkar, honored him with postcards calling him a revolutionary hero.

- Savarkar’s Support: Savarkar, who guided Dhingra, refused to condemn the act, calling for fair treatment. He saw Dhingra as a true patriot who struck at the heart of British espionage.

- Lasting Impact: Dhingra’s act shook the British, leading to the closure of India House, but it also ignited the spirit of resistance. His sacrifice kept the freedom movement alive.

The Truth Must Be Told

The story of Madan Lal Dhingra is not what history books teach. He did not kill Wyllie out of vague anger or revenge for British rule. He killed him because Wyllie was a dangerous spy, secretly working to crush India’s freedom fighters. Wyllie’s secret police, informants, and schemes like the “home for Indians” were choking the revolution. Dhingra’s act was necessary to protect Savarkar, India House, and the dream of a free India. The British hid this truth to save face, and even some Indian leaders turned away from Dhingra’s sacrifice. But the truth is clear: Madan Lal Dhingra was a hero who gave his life to stop a spy and keep India’s fight for freedom alive. His story deserves to be told, not as a footnote, but as a shining example of courage and patriotism.

======== Article Ends Here =======

Note: Evidence of Wyllie’s Spying Activities (My articles are based on facts, here are the sources based on which this article is written).

Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie was a British Indian Army officer and political aide-de-camp to the Secretary of State for India, Lord George Hamilton. Several sources confirm that he was involved in intelligence-gathering activities targeting Indian nationalists in London, particularly those associated with India House, a hub for revolutionary activities led by figures like Shyamaji Krishnavarma and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

Wyllie was the head of a secret police unit tasked with monitoring Indian revolutionaries in Britain.

Richard James Popplewell’s book Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire, 1904-1924 (1995) provides scholarly backing, stating that Wyllie was involved in intelligence operations targeting Indian nationalists in London, particularly those at India House, which was under Scotland Yard surveillance due to its radical activities.

A document from satyashodh.com cites a Scotland Yard report forwarded by Wyllie, which contained details of Savarkar’s alleged speeches at secret India House meetings. The report notes that the evidence was obtained confidentially and could not be publicly disclosed, indicating covert surveillance. It also mentions Wyllie’s trip to Paris to gather information about Savarkar, Harnam Singh, and others, underscoring his active role in tracking revolutionaries.

The same source suggests Wyllie initiated a “home for London Indians to make them loyal,” a strategy perceived by revolutionaries as an attempt to counter their radicalism through surveillance and co-optation.

The Indian Sociologist, a nationalist publication edited by Shyamaji Krishnavarma, described Wyllie and Lee Warner as “old unrepentant foes of India” as early as October 1907, indicating that Indian revolutionaries viewed him as a significant adversary due to his intelligence activities.

David Garnett’s memoir The Golden Echo (1953) indirectly supports this by describing the tense atmosphere at India House, where Savarkar and others were aware of being watched, though it does not explicitly name Wyllie as the orchestrator.