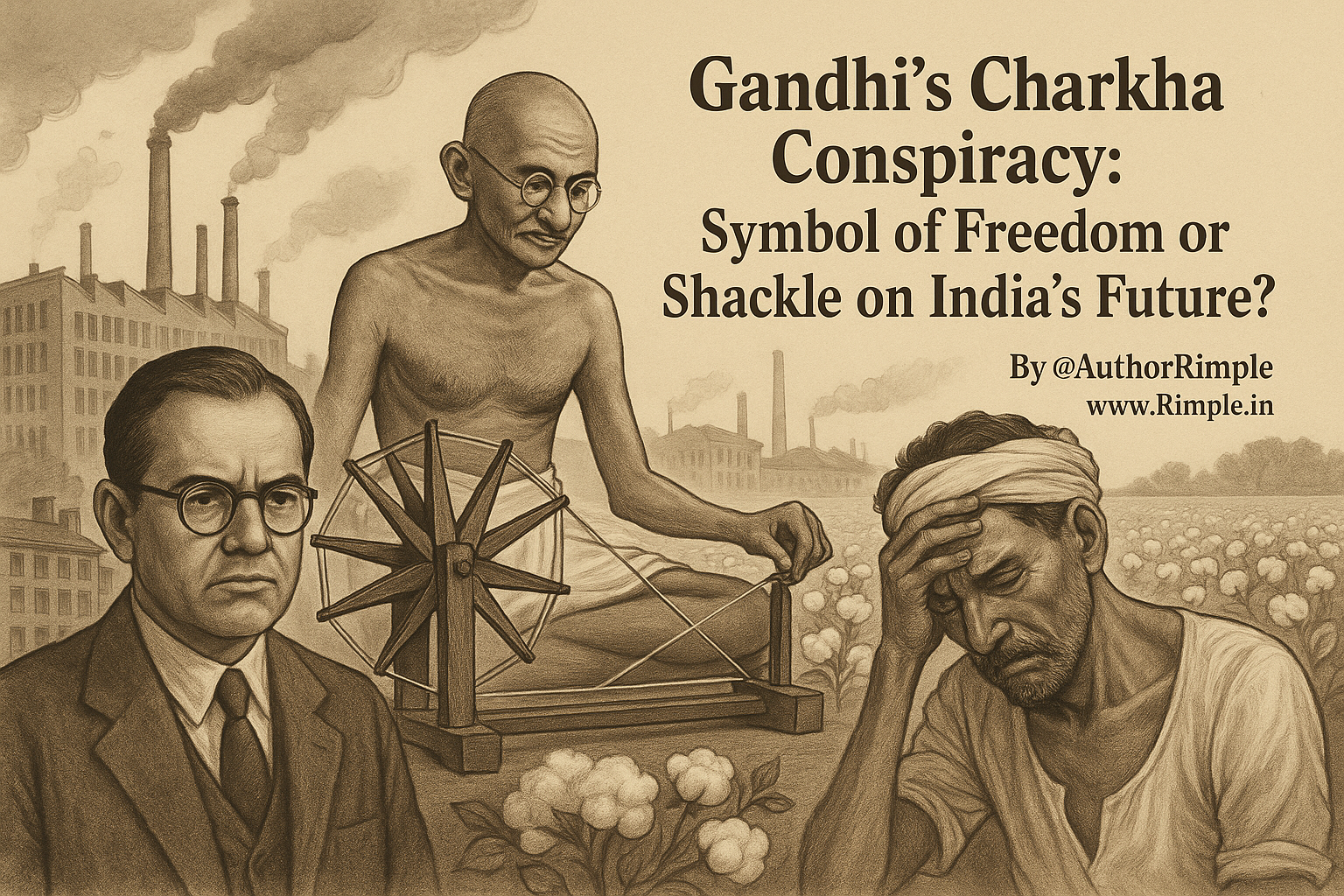

MK Gandhi is often celebrated for his role in India’s freedom struggle, but not everyone saw him as a hero. Some, like the great industrialist Shantanurao Laxmanrao Kirloskar, believed Gandhi’s ideas hurt India more than they helped. In his autobiography, Cactus and Roses, Kirloskar shared his frustration with Gandhi’s focus on the charkha (spinning wheel) and strikes, which he saw as roadblocks to India’s growth. This article explores why Gandhi’s policies, especially the charkha movement, were seen by some as anti-Indian, favoring British interests and harming farmers and industrialists alike. By connecting the dots, we uncover a side of Gandhi that raises serious questions about his legacy.

The Charkha: A Symbol of Self-Reliance or Economic Ruin?

Gandhi promoted the charkha as a tool for swadeshi, urging Indians to spin their own cloth and boycott British textiles. He believed this would make India self-reliant and weaken British rule. But the reality was far more complicated.

- Hurting Cotton Farmers: Indian cotton farmers were already crushed by the British Ryotwari system, paying up to 60% of their crop as tax. The charkha reduced demand for raw cotton by encouraging people to spin at home instead of buying mill-made cloth. This meant less cotton was needed for Indian mills, leaving farmers with surplus crops that the British could buy at dirt-cheap prices. Gandhi’s push for hand-spinning indirectly helped British mills in places like Manchester, which got access to cheap Indian cotton while Indian farmers struggled.

- Blocking Industrial Growth: Industrialists like SL Kirloskar, who built the Kirloskar Group into a global engineering giant, saw the charkha as a step backward. In Cactus and Roses, Kirloskar wrote that Gandhi’s followers ignored the power of machines. He believed machines, like his company’s ploughs and pumps, could lift farmers out of poverty by making farming faster and easier. Instead, Gandhi’s focus on hand-spinning kept India stuck in a pre-industrial era, slowing down progress.

- A Misguided Ideal: Kirloskar argued that Gandhi’s idea of self-reliance—spinning cloth and living simply—was unrealistic. He saw it as a “Gandhian heresy” that ignored how Britain’s strength came from machines, not handwork. When India was colonized, it was a country without machines, overpowered by a nation that had them. Kirloskar believed India needed more factories and technology, not charkhas, to become strong and free.

Strikes: Disrupting Indian Industry

Gandhi’s call for strikes during movements like Non-Cooperation (1920–22) aimed to disrupt British rule, but they also hurt Indian businesses. Workers in cities like Bombay and Ahmedabad, inspired by Gandhi, left their jobs in mills and factories to join protests or spin khadi. This caused chaos for Indian industrialists who were trying to build a modern economy.

- Kirloskar’s Frustration: In Cactus and Roses, Kirloskar described how he disagreed with Gandhi’s followers who saw strikes and khadi as patriotic. He believed these actions weakened Indian businesses, which were already struggling under British taxes and competition. For example, textile mills in India faced losses when workers stopped production, while British mills continued to profit from cheap Indian cotton.

- A Divided Vision: While Gandhi saw strikes as a way to unite Indians against the British, industrialists like Kirloskar saw them as divisive. They wanted to create jobs and wealth through factories, but Gandhi’s focus on village economies and hand-spinning clashed with their vision of a modern, industrialized India.

Gandhi’s Ties to the British: A Spy or a Pawn?

Some voices, both in history and today, have gone further, suggesting Gandhi wasn’t just misguided but actively worked in Britain’s favor. While calling him a “British spy” may sound extreme, there are reasons people question his loyalty to India’s interests.

- Early Life in South Africa: Gandhi spent 21 years in South Africa, where he worked as a lawyer for wealthy Indian merchants and even supported the British during the Boer War by organizing an ambulance corps. Some argue this showed his willingness to align with British interests when it suited him.

- Suspicious Timing: Gandhi’s return to India in 1915 coincided with a time when the British needed to control growing unrest. His non-violent approach, while inspiring, often defused revolutionary movements that threatened British rule more directly. For example, during the Non-Cooperation Movement, Gandhi called off protests after the Chauri Chaura incident in 1922, disappointing those who wanted a stronger fight.

- The Manchester Statue: In 2019, a statue of Gandhi was unveiled in Manchester, a city built on the wealth of its textile mills, which profited from India’s cotton. To critics, this statue is a bitter irony, representing not peace but the suffering of Indian farmers whose cotton fed British mills while they starved under heavy taxes.

Gandhi’s Statue in Manchester. Why would British install his statue here? Now you know it. Also, why Britishers have not installed statues of Subhash Chandra Bose or Bhagat Singh or other REAL FREEDOM FIGHTERS? Do read some eye-opening articles in the “Also Read” section at the end of this article.

The Farmer’s Plight: Robbed in Daylight

Gandhi’s charkha was meant to empower rural India, but it often left farmers worse off. The British controlled India’s cotton trade, buying raw cotton at low prices and selling expensive cloth back to Indians. By reducing demand for mill-made cloth, the charkha made it harder for Indian mills to compete, leaving farmers with fewer buyers and lower prices.

- Taxation Torture: The Ryotwari system forced farmers to pay 60% of their crop as tax, leaving them with little to survive. Gandhi’s focus on hand-spinning didn’t address this root problem and instead shifted focus to symbolic acts like wearing khadi.

- A False Promise: Gandhi promised that spinning would make villagers self-sufficient, but spinning a few hours a day couldn’t replace the income lost from selling cotton. Farmers were caught between British exploitation and Gandhi’s unrealistic vision, leading some to call his policies a “daylight robbery” of their livelihoods.

Kirloskar’s Vision: Machines for a Strong India

Unlike Gandhi, SL Kirloskar believed machines were India’s path to prosperity. In Cactus and Roses, he described how his company’s pumps and engines helped farmers grow more crops with less effort. He saw technology as a way to lift India out of poverty, not keep it tied to outdated traditions.

- Building an Empire: Starting with his father’s small engine business, Kirloskar expanded into a global conglomerate, producing everything from pumps to tractors. He graduated from MIT, bringing world-class engineering knowledge to India.

- A Practical Patriot: Kirloskar didn’t join political protests but served India by creating jobs and machines. He believed this was a better way to fight poverty and British control than spinning cloth or staging strikes.

- Clashing with Gandhians: Kirloskar often debated Gandhi’s followers, who saw machines as enemies of the poor. He argued that machines, like his company’s ploughs, saved time and labor, helping farmers escape the cycle of poverty. His magazine, Kirloskar, became a platform to share these ideas, challenging Gandhi’s vision.

The Dark Side of Gandhi’s Legacy

Gandhi’s image as a saintly leader hides a troubling side. His policies, while well-intentioned, often played into British hands. By focusing on the charkha, he indirectly helped British mills get cheap cotton. By calling for strikes, he disrupted Indian industries trying to compete with the British. And by promoting non-violence over revolution, some argue he softened India’s fight for freedom.

- A British Ally?: Critics point to Gandhi’s meetings with British officials, like Viceroy Lord Irwin, and his willingness to negotiate as signs he was too cozy with the colonizers. Some even claim his non-violent approach was a way to keep India’s rebellion under control, serving British interests.

- Ignoring Industrialists: Leaders like Kirloskar, who wanted to modernize India, felt sidelined by Gandhi’s focus on villages. This created a divide between those who dreamed of an industrialized India and those who followed Gandhi’s back-to-basics approach.

- A Costly Symbol: The charkha became a powerful symbol of resistance, but at what cost? It distracted from building factories and infrastructure that could have made India truly self-reliant. Gandhi’s vision of a simple, village-based economy clashed with the modern world, leaving India unprepared for the industrial age.

Conclusion: A Misguided Hero

Gandhi’s charkha and strikes were sold as tools for freedom, but they came at a heavy price. SL Kirloskar, in Cactus and Roses, saw through the romantic haze of Gandhi’s ideas, warning that they held India back from true progress. Farmers suffered under British taxes and low cotton prices, while industrialists struggled against strikes and a lack of support. The statue in Manchester stands not as a tribute to peace but as a reminder of the hunger and sweat of farmers caught in the charkha’s trap. Gandhi may have meant well, but his policies often helped the British more than India. Kirloskar’s vision of machines and industry, not spinning wheels, was the real path to a strong, free India. History shows us that heroes can be flawed, and Gandhi’s legacy is a tale of good intentions gone wrong.

Also Read: